In October 25th, 1760, King George II of Great Britain passed away. He went to the close stool after drinking his cup of hot chocolate and collapsed on the floor shortly after. By the time Princess Amelia could reach him, the king had died.

The postmortem examination of his body would reveal dissections of the aortic arch and into the pericardium (the sack that surrounds the muscular body of the heart and the roots of the body’s great vessels).

This body failure would come to be known in 1802 as an aortic dissection.

Description

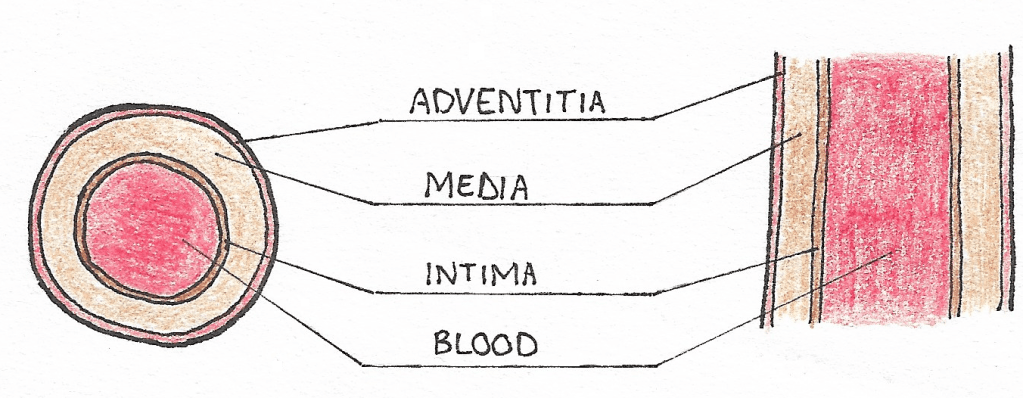

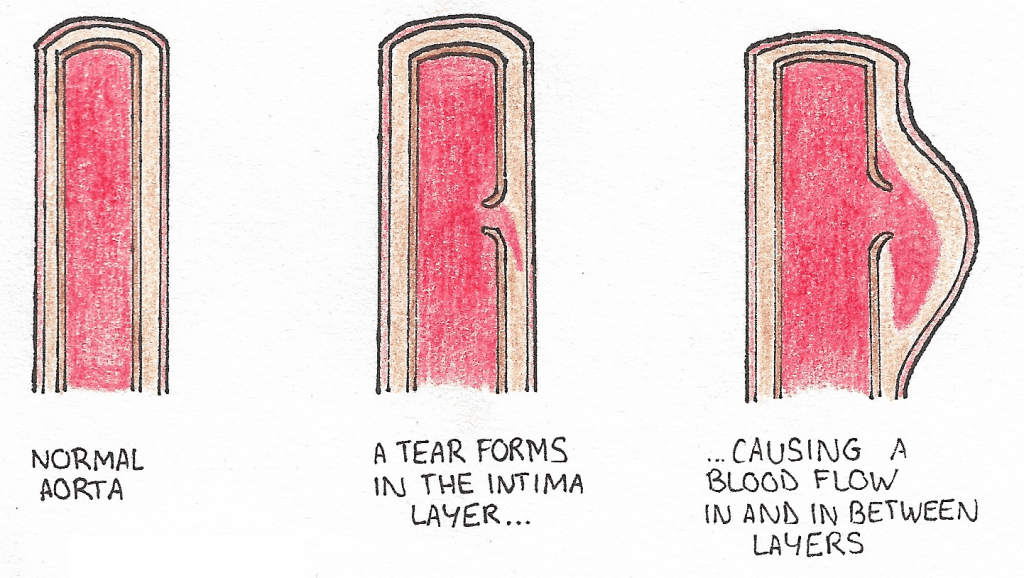

The aortic dissection is a condition in which a tear in the innermost layer of the aorta appears. Just like the skin, the aorta wall is composed of three layers: the intima, which is closest to the blood flow, the intermediate one that is called the media, and the adventitia. Tearing of the intima causes the blood to flood in the media layer and in between layers, resulting in a deviation of the normal blood flow. It may also reduce the width of the true lumen of the aorta, resulting in a weaker blood flow to other organs.

Schema presenting the three layers of the aortic wall

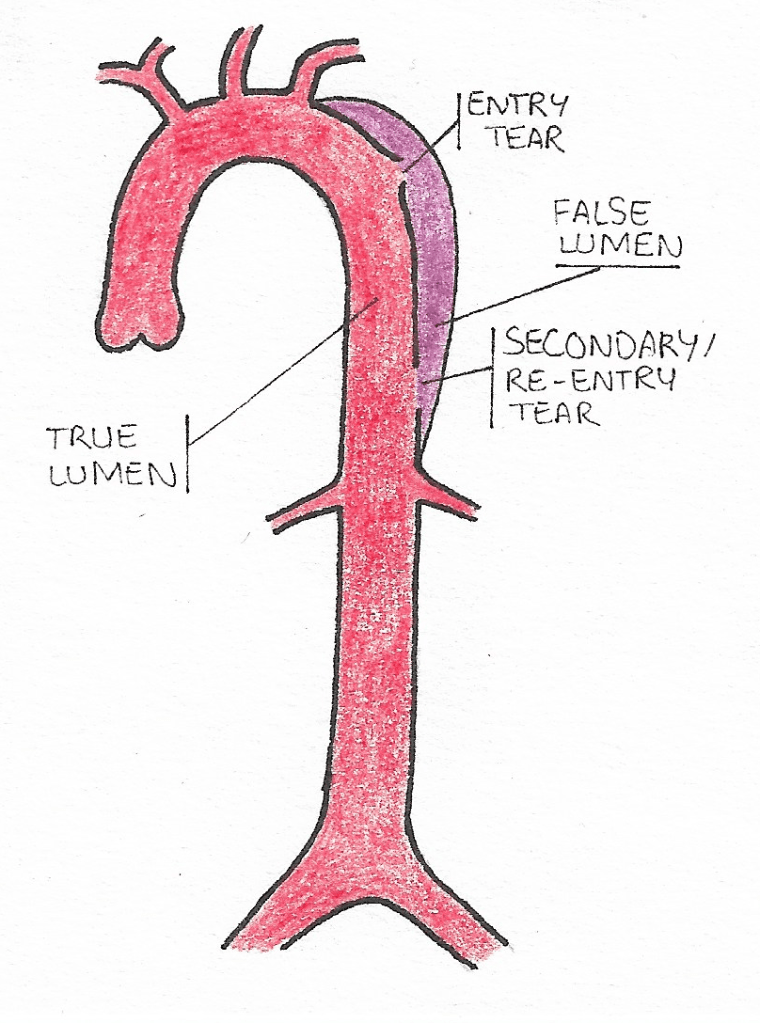

Because the blood is deviated from its original course into the false lumen, some organs may suffer from insufficient blood supply. The fluid accumulation in the false lumen may also result in tearing of other vessels.

When a tear occurs in the intima layer (closest to the blood flow), it creates an opening in which the blood flow can over time enter and deviate from its original course.

Sometimes the pressure induced by the blood trapped in the false lumen causes secondary tears to form in the intima, resulting in the returning of the blood in the true lumen.

Sometimes the pressure induced by the deviated blood flow causes a secondary tear to form, from which the blood retrieves its original path.

Epidemiology

This rare condition is thought to affect 3 out of 100,000 people every year and is more common among men (around 65% of cases). However, researchers believe this rate to be higher, as dissection is often discovered after the patient’s death. They also believe that the incidence of the condition may be rising.

The average diagnosis age is 63 but around 10% of cases happen to people below 40. In females before 40, half of aortic dissections happen during pregnancy (typically during the third trimester or early postpartum phase).

Symptoms

- Most people affected with aortic dissection report a sudden and severe chest pain (it is said to feel like a stabbing or tearing sensation).

- Dyspnea (trouble breathing), excessive sweating and vomiting are frequently observed in patients with aortic dissection.

- Another common symptom is hyper or hypotension, depending on the dissection type (we’ll cover this later in the post).

- Aortic insufficiency is a frequent sign and can be observed by an audible heart murmur. Its loudness depends however on the blood pressure and may be inaudible if the patient suffers from low pressure.

- Heart attacks happen in 1 to 2% of aortic dissections. It happens when the coronary arteries (which supply the heart with oxygenated blood) are impacted by the dissection.

- Pleural effusion may be observed. The term is used to describe fluid effusion in the space between the lungs and the chest wall) and is either due to fluid from an inflammatory reaction around the aorta or blood from a rupture of the aorta.

Classification

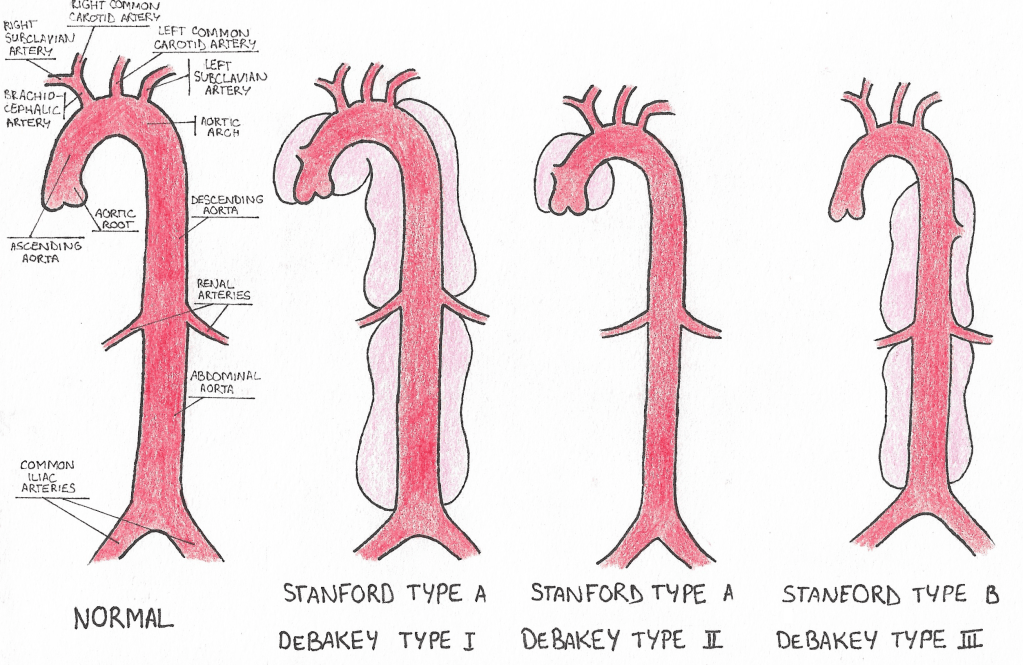

Two systems are widely used to classify aortic dissections: the Stanford model, and the DeBakey (named after the inventor of the surgery for aortic dissections) model.

Stanford uses two categories and labels dissections with type A if they affect the part prior to the aortic arch, and type B in they do not. DeBakey makes a distinction between dissections that only involve parts of the aorta before the arch (type I) and the ones that propagate beyond the arch (type II). Type III is equivalent to Stanford’s type B and therefore happens after the arch.

Classifications of aortic dissections and comparisons between the classification models

Because of their proximity to the heart, type A dissections may cause a failure of the aortic valve and induce aortic insufficiency (the valve cannot fully close anymore and causes blood to flow in the opposite direction, causing a heart fatigue).

Without any treatment, most people affected with type A dissections die within 3 days, and death occurs within a month for those with type B.

Causes

- Some genetic and/or hereditary diseases and conditions increase the risk of developing aortic dissections: Elhers-Danlos, Marfan’s syndrom and aortic narrowing to name a few.

- Uncontrolled and/or untreated hypertension is to be blamed in 72 to 80% of cases.

- Chest trauma (such as in car accidents) may provoke dissections, and smoking and usage of illicit drugs such as cocaine and methamphetamine are a risk factor.

- Atherosclerosis (build up of fat, cholesterol and other substances that prevent blood from flowing freely), aortic dilation, infection and inflammation are common causes for aortic dissections as well.

Diagnosis

While it’s helpful to have a good history of the patient’s health condition, imaging techniques are often required to fully access the dissection type and gravity. Images of the aorta will help assessing the tear’s dimensions, location and whether it is likely to induce insufficient blood flow to various organs.

There is no definitive imagine technique and the practitioner will choose between MRI, Computed Tomography, X rays and ultrasounds depending on the patient’s health, the likelihood of the prediagnosis (how sure are we that it’s a dissection we’re dealing with here) and of course, the imaging device’s availability.

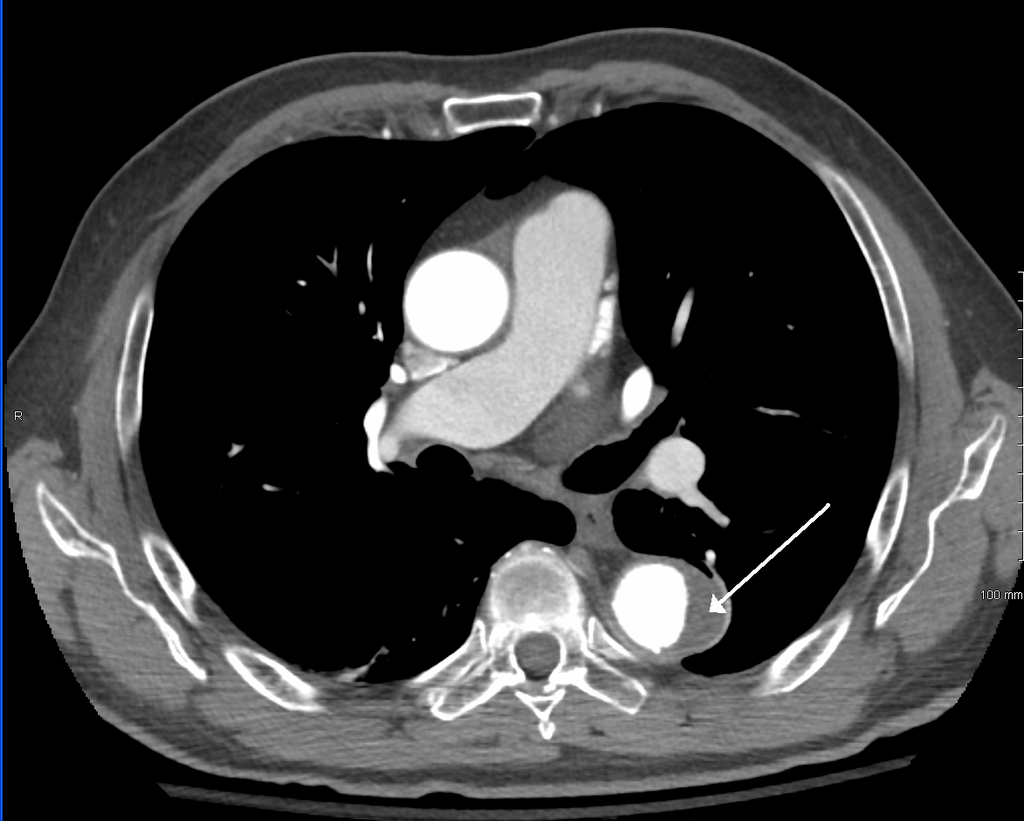

The image below presents what a CT scan looks like for a patient with a type B dissection (author James Heilman, MD): the area outlined by the arrow is the dissection’s false lumen. This new route shrinks up the aorta and decreases the blood supply in the aorta (the white part next to the false lumen, which is quite smaller in comparison to how wide the aortic root is at the center of the image):

CT scan presenting a dissected aorta. The bright round shape is the true lumen, where blood naturally flows. The area pointed by the arrow is the false lumen, where blood can accumulate and create clots, or flow and build up pressure later on the intima wall to create a secondary tear, enabling the blood to re-enter the true lumen.

In some cases a measurement of blood D-dimer may be useful in assessing the diagnosis. D-dimer is a small protein fragment that is produced after a blood clot is destroyed by the body. High levels of blood D-dimer may indicate that the patient suffers from a dissection (because it means there is a lot of clogged blood to get rid of).

The test has to be done quickly after first symptoms are observed to be deemed helpful though, which is why the American’s heart association advises against using D-dimer measurement to rule out possible dissections.

Treatment

There are two ways of treating dissections, and preferring one over the other will depend on the dissection’s gravity. Medication is commonly used so as to reduce the blood pressure (in cases where the patient suffers from hypertension) and prevent the tear(s) from getting bigger. Should the dissection be deemed acute and/or present one or more complications, medication is not enough and surgery is required. Type A dissections are most commonly treated with open heart surgery, where the damaged part of the aorta is replaced by a tube made from Dacron (a polyester fabric). If the aortic valve is affected as well, it is replaced by a prosthesis (this procedure is known as TAVI/TAVR, or transcatheter aortic valve replacement. I’ll probably write about this in a future post).

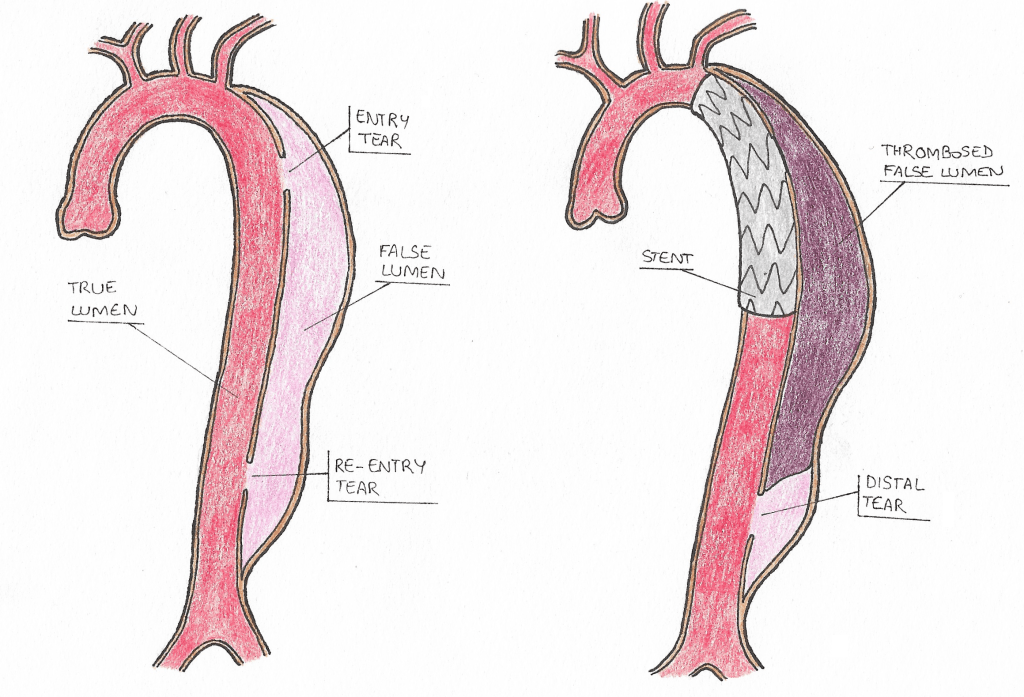

Type B dissections are usually treated with endovascular surgery, and therefore is much less invasive. A hole is cut in the thigh so that one of the thigh’s arteries is reachable. From there, a stent composed of a metal mesh and synthetic fabric is inserted in the hole with a catheter (a plastic tube). With the help of imaging devices, the surgeon moves the catheter so that the stent is placed where the tear is.

Once the stent is placed, the catheter is removed. With this prosthesis (referred to as a stent), the blood is prevented from flowing into the false lumen and with time, the blood trapped in the false lumen clogs and/or the walls close on the stent, as shown below:

During endovascular surgery the surgeon will navigate through one of the thigh arteries and push a catheter up to the aorta to position the stent where the entry tear is. Over time the blood stuck in the false lumen will clot, resulting in a thrombose. The lower tear remains and because of the blood pressure, it does not re-enter through this channel.

Takeaway

Aortic dissection is a severe condition in which tears are formed in the aorta wall, causing the blood to flow and accumulate in undesired places and may result in insufficient blood flow to various organs.

As some of its symptoms overlap with other conditions, it is commonly mistaken for heart attacks. Immediate intervention is usually required to prevent the patient’s death and a close follow up is needed to ensure that blood pressure levels remain low enough and that further complications do not arise.

Citations

- Nienaber, CA; Clough, RE (28 February 2015). “Management of acute aortic dissection”. Lancet. 385 (9970): 800–11. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61005-9. PMID 25662791. S2CID 34347018.

- Criado FJ (2011). “Aortic dissection: a 250-year perspective”. Tex Heart Inst J. 38 (6): 694–700. PMC 3233335. PMID 22199439.

- White, A; Broder, J; Mando-Vandrick, J; Wendell, J; Crowe, J (2013). “Acute aortic emergencies–part 2: aortic dissections”. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal. 35 (1): 28–52. doi:10.1097/tme.0b013e31827145d0. PMID 23364404.

- Olsson Ch.; Thelin S.; Ståhle E.; Ekbom A.; Granath F. (2006). “Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm and Dissection. Increasing Prevalence and Improved Outcomes Reported in a Nationwide Population-Based Study of More Than 14 000 Cases From 1987 to 2002”. Circulation. 114 (24): 2611–2618. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.630400. PMID 17145990. Archived from the original on 2016-08-07.

- Daily PO, Trueblood HW, Stinson EB, Wuerflein RD, Shumway NE (Sep 1970). “Management of acute aortic dissections”. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 10 (3): 237–47. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(10)65594-4. PMID 5458238.

- Dissection aortique, Service de cardiologie CHUV [FR]

Leave a comment